Pablo Picasso - Nature morte

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Nature morte

signed and dated 'Picasso 25. Av. 37.' (centre right)

oil on canvas

15 x 24 1/8 in. (38 x 61.1 cm.)

Painted on 25 April 1937

Nature morte

signed and dated 'Picasso 25. Av. 37.' (centre right)

oil on canvas

15 x 24 1/8 in. (38 x 61.1 cm.)

Painted on 25 April 1937

There is an intensely poetic atmosphere to Nature morte, painted in 1937. Stars are glowing in the night sky, while the foreground is dominated by the accoutrements and accessories of a leisured and contemplative evening. Pipe and book lie alongside a drink and a candelabra, hinting at the passing of an evening of solitary pleasures, both of the mind and of the body. The lyricism of the scene is heightened by the swirling curlicues of the balcony in the background, as though this evening were being spent in the countryside, rather than in Paris. As though it was the Eighteenth Century and a time of peace, rather than a metropolis, with the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War.

While there is undoubtedly an air of whimsy to Nature morte, the picture - both in terms of composition and content - also reveals a great sophistication, perhaps reflecting the influence of Picasso’s still new relationship with the photographer Dora Maar. In contrast to both his wife Olga and his lover Marie-Thérèse, Dora was an intellectual, sharp, cosmopolitan, twisted, dark and intriguing, and it is perhaps more a reflection of the evenings that he spent in her company, or at least influenced by the habits of his new lover, that Nature morte shows book, pipe and view. The jutting forms that Picasso has used to render many of the elements in Nature morte, in this context, can be seen to prefigure her subsequent repeated depiction of La femme qui pleure, the Weeping Woman, the embodiment of all Picasso’s anguish at the situation in his homeland and, increasingly, in the world at large.

Discussing the presence and influence of the conflicts that ravaged first Spain and then, in the Second World War, vast swathes of the globe, Picasso stated: ‘I have not painted the war because I am not the kind of painter who goes out like a photographer for something to depict. But I have no doubt that the war is in these paintings I have done. Later on perhaps the historians will find them and show that my style has changed under the war’s influence. Myself, I do not know’ (Picasso, quoted in S.A. Nash, ed., exh. cat., Picasso and the War Years 1937-1945, New York, 1998, p. 13).

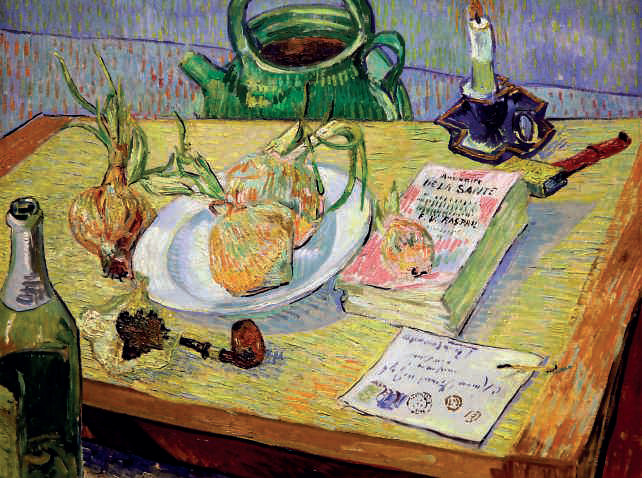

Guernica aside, he did not paint overt images of the battles and fights, yet his own anxieties necessary came to show through, as though by X-ray. In Nature morte, it is clear in the jutting forms of which the various elements are composed. This angularity is all the more jarring because of its contrast with the bold colourism that Picasso has used in this painting, which is sensitive and lyrical despite its boldness. The yellows and reds, especially the scratched-away lines that articulate the balcony railing and the stars, have a vibrant energy that adds a shimmering sense of magic to the scene. This is heightened by the inclusion of these over-sized stars in the first place they appear to be the Picasso-esque re-imagining of those that fill the sky of Vincent van Gogh’s celebrated painting The Starry Night, painted in 1889. This sense of magic is also one of romance - the scattered objects introduce a feeling that the viewer has stumbled across someone’s private world, an atmospheric retreat, a place of meditation and inspiration.

Many of Picasso’s paintings and drawings from this period depict still life subjects. A comparison with any of the works leading up to the 25 April, when this work was painted, shows that this picture is characterised by a fullness and sense of finish that many of the others lack, a factor that is increased by the careful attention paid to the star-filled background. It has been hypothesised that this focus on still life, and the concurrent pictures of the artist and model in the studio, were a deliberate exploration of Picasso’s self-indulgent and world-denying tendencies while the conflict raged in Spain, and that these themes were going to be explored on a far larger scale in his projected mural for the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World Fair that year. Picasso had initially been approached with the request for a mural decoration as early as January 1937. The group that made the request included Louis Aragon, as well as the architect for the pavilion, Josep Lluis Sert, and various Spanish dignitaries.

Picasso’s works from this point focus, as mentioned above, on still life and on the artist and model in his studio. Both of these convey a sense of the self-encapsulated, sensuous and self-indulgent world of the artist, which led Herschel B. Chipp to claim, in his Picasso’s Guernica: History, Transformations, Meanings, that the artist and his model in a studio would have been the original theme for these murals, exploring his own guilt to some degree, and bending it into the form of a highly personalised statement. Certainly, most of Picasso’s pictures are the results of his own feelings, sensations, thoughts and emotions, and he usually eschewed subjects which he did not feel directly. The war was around the corner, and yet perhaps remained somehow abstract and distant to the artist at this point. While Chipp’s theory has been accepted by some and rejected by others, it is certainly the case that Picasso was painfully aware of his lack of direct intervention in the situation in Spain. Only the previous year, worried by the escalating political situation in Spain, he had even asked Eluard to go as his substitute to accompany a travelling retrospective of his works that was shown in his native country. Picasso was clearly conscious of his inability to fight, although he helped in many other ways, supporting many refugee causes, raising funds, creating publicity. And ultimately, the murals that he would provide for the Spanish Pavilion would be a publicity coup, as is clear from the fact that the resultant masterpiece, Guernica, continues to have resonance to this day.

Nature morte may well tie into the artist’s exploration of his self-indulgent lifestyle at the time, and therefore may even relate to some of Picasso’s own ideas for the murals for the Spanish Pavilion. It is through one of the tragic ironies of history, though, that the very day after Nature morte was painted, inspiration for the mural would come with all too much force. For it was on the 26 April 1937 that the planes of the German Condor Legion bombed the Basque town of Guernica, killing over a thousand people. This atrocity became Picasso’s inspiration. He fuelled his outrage, anger and horror into Guernica, a searing statement, a scream of sympathy and of indignation. Painting Guernica took a great amount of time, and the theme and various aspects of the composition would come to occupy almost all of his attention for the following months, meaning that Nature morte marks the very end of an entire period of Picasso’s art before a change of direction that would leave its mark on the artist for a long time to come.

|

Vincent van Gogh, Still-Life with Drawing Board and Onions, 1889. Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo.

|

|

Pablo Picasso, Nature morte, 1937. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven.

|

|

Pablo Picasso, Nature morte à la bougie, 1937. New Orleans Museum of Fine Art.

|

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment