Edward Coley Burne-Jones & Charles Fairfax Murray - Venus Epithalamia

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt., A.R.A. (1833-1898) and Charles Fairfax Murray (1849-1919)

British

Venus Epithalamia

titled on the painted scroll lower right

watercolour and gouache with gold paint on paper

Unframed: 37.8 by 27.3cm., 14½ by 10¾in.

Framed: 55.5 by 45.3cm., 21¾ by 17¾in.

Charles Handley Read (1916-1971), London

Sale: Sotheby’s, Belgravia, 29 June 1976, lot 270

Roy Miles, London

Julian Hartnoll, London, 1985

Rudolf Lang, until 1993

Peter Nahum at The Leicester Galleries, London

Purchased from the above by the present owner in 1994

Martin Harrison and Bill Waters, Burne-Jones, London, 1973, p. 96

John Christian, ‘Burne-Jones Studies’, in The Burlington Magazine, February 1973, vol. 115, p. 106, illustrated fig. 46

Stephan Wolohajian (ed.), A Private Passion: 19th Century Paintings and Drawings from the Greville L. Winthrop Collection, Harvard University, New Haven, 2003, pp. 364-365

Fiona McCarthy, The Last Pre-Raphaelite, London, 2011, p. 221

Liana De Girolami Cheney, Edward Burne-Jones’ Mythical Paintings: The Pygmalion of Pre-Raphaelite Painters, Bern, 2014, p. 149, illustrated fig. 10

David B. Eliott, A Pre-Raphaelite Marriage – The Lives and Works of Marie Spartali Stillman & William James Stillman, Woodbridge, 2006, pp. 69-70

Catalogue Note

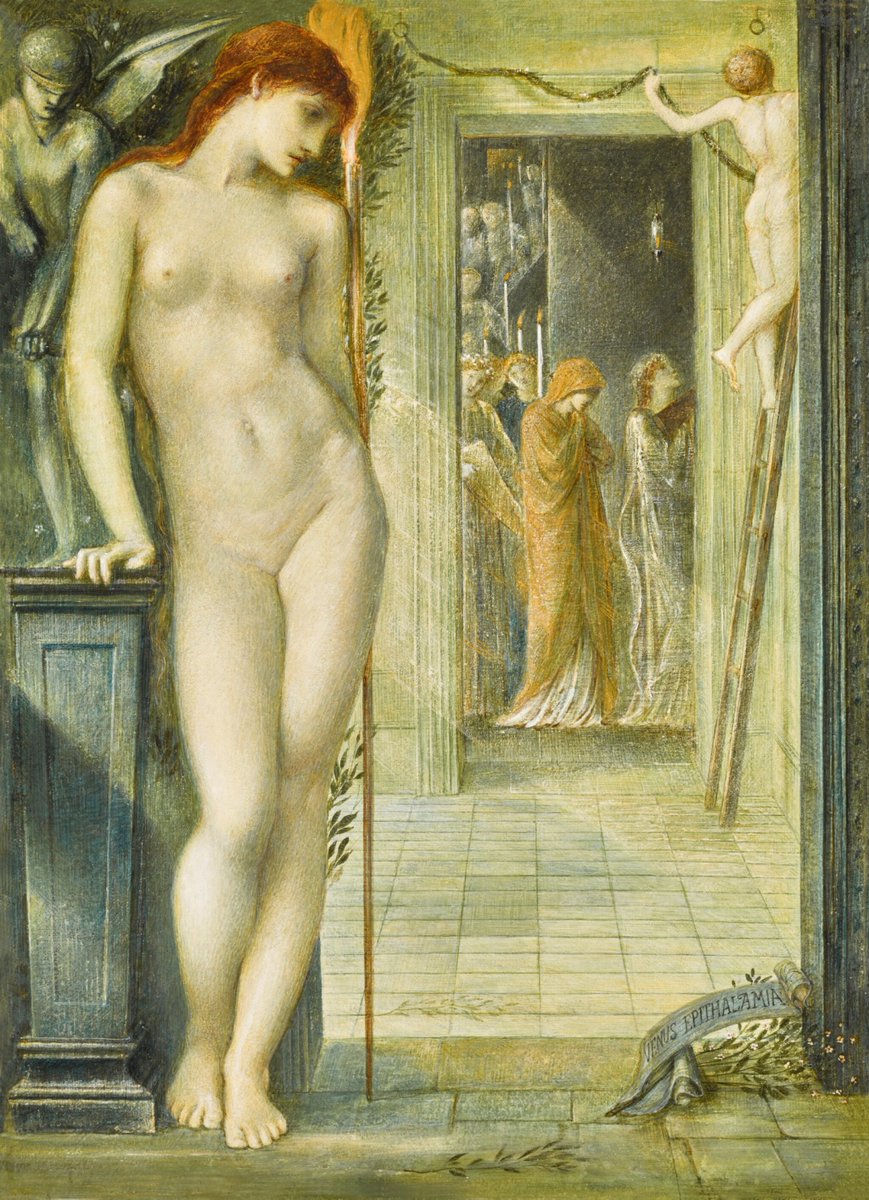

In the doorway of a marble courtyard, the languid and naked figure of Venus watches the procession of a bride dressed in red and accompanied by musicians and bridesmaids descending a stairway from a tower. Golden sunlight streams into the courtyard where a nude boy is hanging garlands in celebration of the marriage ceremony. He teeters precariously on a ladder, perhaps suggesting the dangers of love. The sprigs of myrtle that litter the floor, may also suggest the victims of unrequited love, broken and cast aside. Myrtle was a plant sacred to Venus because its evergreen foliage was symbolic of everlasting love and marital fidelity but it also has poisonous berries. Behind the Goddess is a statue of her son Cupid, blindfolded because Love is blind and pulling back the string of his bow to shoot his arrows into the hearts of unwitting lovers. Venus’s melancholy expression can be explained by her unhappy marriage to Vulcan, the God of the Forge and her adulterous love for Mars, the God of War. She holds a flaming torch which symbolises both Vulcan’s fiery caverns and Venus’ passion for Mars. With this flame she will ignite the fires of desire.

The first version of Venus Epithalamia (Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts) was painted in watercolour and gouache on linen in 1871 as a gift for Marie Spartali (lot 10) on the occasion of her marriage to the American journalist and photographer, William James Stillman. It was commissioned by Marie’s aunt Euphrosyne Cassavetti, wife of the wealthy shipping magnate Demetrios Cassavetti. Following the death of Demetrios in 1858, Euphrosyne created a salon for artists, politicians, writers and radicals at her fashionable house at Tulse Hill in South London. Euphrosyne’s wealth and eccentricity gained her the soubriquet ‘The Duchess’. She was a leading figure in the Anglo-Greek community in London, which included her brother Alexander Constantine Ionides, one of London’s greatest patrons of the arts. She was also an important Pre-Raphaelite patron and a friend to Burne-Jones after she commissioned a watercolour version of Cupid Finding Psyche in 1866.

The wedding of Marie Spartali, the younger daughter of the wealthy Greek consul Michael Spartali, was a much-anticipated event, although her parents were concerned by her choice of husband. William Stillman had little money and a precarious career whose first wife had committed suicide. Maria was wealthy, a talented amateur artist and strikingly beautiful. Her statuesque beauty had been the inspiration for a series of pictures by Rossetti and Spencer Stanhope and photographs by Julia Margaret Cameron. She was so beautiful that the poet Swinburne could barely look at her without crying and even the notoriously difficult Whistler was like a child in her presence. Burne-Jones himself painted her as Danae at the Brazen Tower of 1888 (Glasgow City Art Gallery) depicting the mother of Perseus watching the building of a tower in which her father would imprison her to prevent her from being seen by any man. The composition of this painting and the pose of Danae standing at the portal of a courtyard watching figures within, is very similar to Venus in Venus Epithalamia and it is likely that Burne-Jones had recalled the watercolour he had painted seventeen years earlier for the woman who now posed for Danae. Ironically, Marie Spartali’s version of Venus Epithalamia was sold in 1905 to pay the expenses of her own daughter’s wedding and made its way into the collection now at Harvard University.

The subject of Venus Epithalamia was chosen specifically for the gift because it depicts Venus as the instigator of marriages, an ‘epithalamia’ being a poem or song recited to a bride at the doorway of the bridal chamber on the wedding night. The Roman poet Catullus wrote a famous epithalamium inspired by his love for the poetess Sappho. Epithalamia was also a genre of painting in the Italian Renaissance, where paintings of nudes were given as wedding gifts, there being a popular belief that the ancient Romans had given erotic paintings as gifts to inspire wedding-night passions. Venus was often the subject of these paintings as her nudity was excused by her mythological status as the Goddess of physical beauty and sexual desire.

It may seem odd for Burne-Jones to have painted a melancholy Venus as a wedding gift for a friend but he often bewailed the marriages of the young and beautiful muses who inspired him – his behaviour on the day of his own daughter’s wedding day suggested that it was the worse day of his life when he had to surrender her love to another man. For Burne-Jones, romance, love and desire were complicated and in Venus Epithalamia we see the ambivalence towards love in the powerful tension of the scene.

RIGHT: SIR EDWARD COLEY BURNE-JONES, VENUS DISCORDIA, NATIONAL MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY, CARDIFF

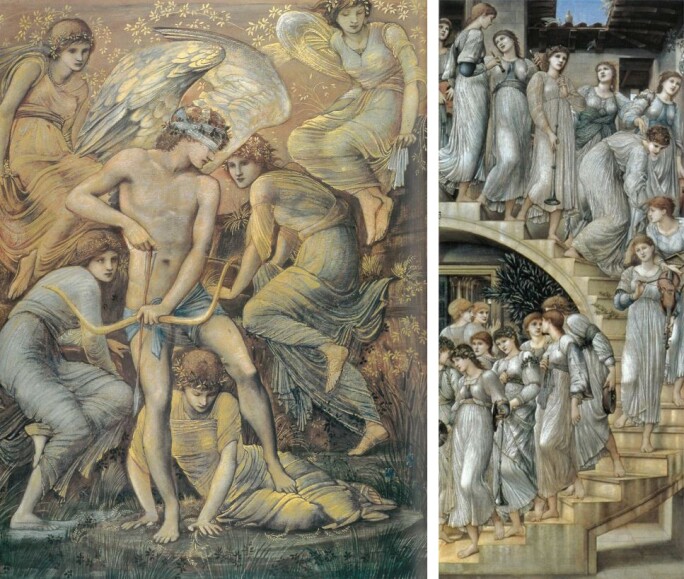

Two contemporary compositions should be particularly considered when studying the symbolism of Venus Epithalamia, the incomplete oil paintings Venus Concordia (City Museum and Art Gallery, Plymouth) and Venus Discordia (National Museum and Art Gallery, Cardiff). These two paintings (and the highly-finished pencil drawings at the Whitworth Museum, University of Manchester) depict Venus as a passive bystander watching the destructive power of love and the harmonies of romance. In one there is violence and the other peace but in both there is tension and in both Venus sits coolly and looks on seemingly without emotion. The same inert reaction can be seen in Venus and Cupid in the background of The Altar of Hymen (Christie’s, London, 17 June 2014, lot 5), another watercolour painted for a wedding gift. Interestingly The Altar of Hymen also exists in two versions (the other was sold Christie’s, London, 11 June 2013, lot 24).

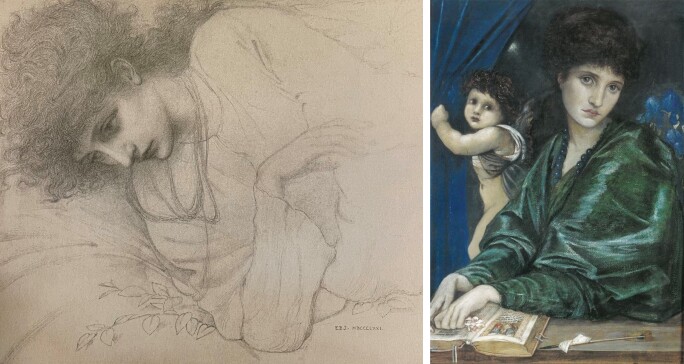

RIGHT: SIR EDWARD COLEY BURNE-JONES, PORTRAIT OF MARIA ZAMBACO, CLEMENS SELS MUSEUM, NEUSS

It is not clear whether Euphrosyne was aware that her own daughter had posed for Venus Epithalamia and that the composition was laden with the symbolism of Burne-Jones’ aching desire for Maria Zambaco and his fear of what damage that passion could do to his own marriage. In 1870 Euphrosyne had commissioned Burne-Jones to paint a portrait of her daughter (Clemens Sels Museum, Neuss) and the resulting gouache, is a hymn to Burne-Jones’ love for his model which had become more intense in the four years since they had met. Euphrosyne could not have failed to notice how Burne-Jones regarded her daughter and she seems to have encouraged their closeness. She had inherited her father's fortune in 1858 and trained in the atelier of Auguste Rodin to be a professional medalist and bronze sculptor in Paris. In 1861 Maria had married Dr Demetrius Zambaco in Paris but he was universally regarded as a man of unsuitable personality for his headstrong and passionate wife. She left her husband in 1865 and moved to London with her two children to live with her mother and to study at the Slade School of Art. She became Burne-Jones’ principal model in the late 1860s and when the two became lovers, she hoped he would leave his wife, the long-suffering Georgiana Burne-Jones. It seems that Burne-Jones became increasingly uncomfortable with Maria’s volatile temperament and did not want to upset the status quo of his marriage. He called-off their affair and left for Rome with William Morris, as recounted by Rossetti in a letter to Ford Madox Brown; ‘Poor old Ned’s affair has come to a smash altogether, and he and Topsy [Morris], after the most dreadful to-do, started for Rome, suddenly, leaving the Greek damsel beating up the quarters of all his friends for him and howling like Cassandra… She provided herself with laudanum for two at least, and insisted on their winding up matters in Lord Holland’s Lane. Ned didn’t see it when she tried to drown herself in the water in front of Browning’s house- bobbies collaring Ned who was rolling with her on the stones to prevent it, and God knows what else.’ Although Georgiana turned a blind eye to her husband’s infatuations with several young women, his relationship with Maria had stepped over the line of what she could tolerate. Maria seems to have accepted that Burne-Jones was not going to leave his wife and the affair was over, but she remained his muse and appeared in many later pictures. She was the inspiration for his greatest work, particularly recognisable in profile as she is in Venus Epithalamia, her fine and melancholic pale features contrasting with her bright golden-red hair - making her the Pre-Raphaelite archetype.

RIGHT: SIR EDWARD COLEY BURNE-JONES, THE ROCK OF DOOM, STAATSGALERIE, STUTTGART

Burne-Jones painted Venus in a contrapposto pose to deliberately evoke the statues of the ancient Greeks, to reflect both Maria Spartali and Maria Zambaco’s heritage. However the languid pose was one that he often asked his models to adopt, with the weight on one foot and the hips and shoulders positioned in a serpentine curve of the spine. The same pose can be seen in The Wheel of Fortune, The Rock of Doom and The Mirror of Venus. Although the flame-red hair and fine profile are unmistakably those of Maria Zambaco it is unlikely that she would have posed nude for Burne-Jones. She had been his lover but she was from the ‘respectable classes’ and unlikely to have posed naked. It is more likely that the toned body was based upon Burne-Jones favourite professional model, Antonia Ciava whose statuesque physique reminded him of the ancient statues of Venus that he admired in the British Museum. Burne-Jones had been wary of painting nudes since the scandal of 1864 when he was critically attacked for his depiction of a male nude in Phyllis and Demophoon at the Old Watercolour Society exhibition that year. Burne-Jones was often criticised for the eccentricities displayed in the drawing of anatomy in his nude studies and in an attempt to improve his drawing of the human body he produced a large number of studies of naked models in repose and in action, encouraged and guided by his old friend George Frederick Watts.

RIGHT: SIR EDWARD COLEY BURNE-JONES, THE GOLDEN STAIRS, TATE

The subject of Venus and that of her son Cupid was one that Burne-Jones painted on many occasions, from her birth from the foam of the sea to her destructive meddling in the relationship between Cupid and Psyche. Some of her earliest appearances in his art were the illustrations made for The Early Paradise in the 1860s. In 1865 Burne-Jones drew a red chalk drawing of The Court of Venus (private collection) depicting Venus and her hand-maidens and in 1873 he painted the famous The Mirror of Venus (Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon) which is arguably his greatest celebration of female beauty. There are elements of Venus Epithalamia which anticipate later paintings, such as the similarity of the bridesmaid’s on the stairs and those in The Golden Stairs begun in 1876 (Tate) and the modest, heavily-draped bride who resembles the bride in The Wedding of Psyche completed in 1895 (Musées Royaux des Beaux Arts de Belgique, Brussels). The figure of blindfolded Cupid arming his bow, also appears in Cupid’s Hunting Fields (Art Institute of Chicago) and the tapestry The Passing of Venus designed in 1898 (Detroit Institute of Arts). One of Maria Zambaco's best-known bronzes, entitled Amour Irresistible depicts Cupid re-loading his bow.

When Euphrosyne saw the earlier version of Venus Epithalamia she was spell-bound by it. According to Marie Spartali, who wrote to her friend Sara Norton on 9 December 1912 on the subject of her gift: ‘Mrs Cassavetti was so pleased with it that after giving it to me she begged to have it back to get it copied for herself, and that Mr Charles Fairfax Murray made the copy that I used to see in her bedroom.’ (letter in the collection of Harvard University). In a letter from Fairfax Murray to Greville Winthrop, dated 19 May 1912 he confirms his involvement in the painting; ‘She [Mrs Cassavetti] liked it so much that she regretted parting with it and a copy was made by me for her before it left the studio’ (letter in the collection of the Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts). It was very usual for Burne-Jones to work in this way and in the late 1860s he employed two permanent studio assistants to help him with his work, Charles Fairfax Murray and Thomas Matthews Rooke – along with several other assistants. Burne-Jones was following the Renaissance model and most of his later works were painted by himself in conjunction with assistants. This is explained more fully online at the Burne-Jones catalogue raisonné.

Comments

Post a Comment